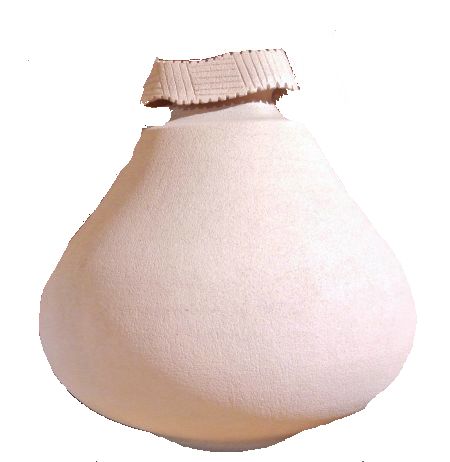

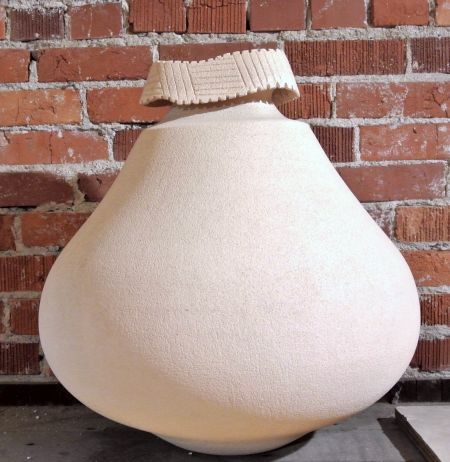

P272 Winnebago contemporary tan clay pot by Winnebago potter Jacquie Stevens. The 20” x 20” tan clay pot has a contemporary “collar” around the top opening.

CALL FOR SHIPPING

Jacquie Stevens pays fastidious attention to the contrasts between the clean undefiled form versus the quiet disturbance of an added material. This artist is one of the most innovative American Indian potters working today.

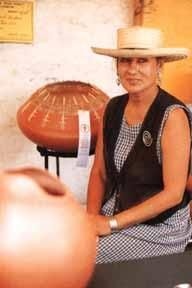

About the artist

Jacquie Stevens,

Jacquie Stevens, a Hochungra or Winnebago Indian, was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1949. She creates asymmetrical pots with a monumental presence and a minimalist feel. Her large, skillfully constructed vessels - augmented with touches of wicker, fiber, and stone - set her apart.

Jacquie was raised by her grandparents on the Winnebago Nebraska Reservation, seventy-five miles north of Omaha. She had clay in her backyard along the Missouri River and was continually making things, particularly unusual clay objects. "But," she says, "if I had known then what I know now, I wouldn't have spent so many years as I did making traditional Winnebago appliqué work on costumes, blanket shawls, and pillows."

She was sent to boarding school in Flandreau, South Dakota, at age thirteen, and then to Haskell Institute, because her family believed in formal education. Later she attended the University of Colorado at Boulder to explore anthropology as a major subject.

After being introduced to aboriginal art from around the world, which Jacquie realized related to her own tribal background, she yearned to investigate further. In I975 she arrived in Santa Fe to enroll in the Institute of American Indian Art with a particular interest in the museum program. There, Otellie Loloma, a Hopi woman respected as one of the greatest teachers in the history of Native arts education as well as a Hopi potter, became Jacquie's mentor and friend. (Otellie was a master in ceramic arts and a graduate of the prestigious Alfred University in New York where she attended classes with her former husband, the jeweler Charles Loloma).

"It must have been fate that made me take a class taught by Otellie. It was like I returned home; clay became my expression. Otellie never told you what to do, she just gave you the basics and let you go. My first pots were lopsided, but Otellie said that she loved them. She always found something beautiful in everything. Otellie taught me that each pot has its own life, personality, character, and form - and that is what set me free. Pottery is like people, every one is different and not perfect. I thought about this and decided it was an important idea. So I developed a new way, an unconventional way, of looking at form."

With the encouragement of Otellie, Jacquie was perhaps the first Indian potter to coil large, off-round vessel shapes. Hers are splendidly simple, with flawlessly scraped and sanded clay surfaces in their natural state - unglazed and unburnished. Because she likes subtle color changes, she uses many varieties of clays in combination with each other or mixed together. She is prone to adding other textures, such as leather, woven reeds, wicker, wood, or stones somewhere on the pristine fired clay form. A favorite clay additive is mica, a mineral flake that sparkles in the sun and adds a shimmer to her plainware pots. Potters in the Southwest have used clay infused with mica, a shiny mineral, since 200 A.D. and her source is in Taos, New Mexico. She pays fastidious attention to the contrasts between the clean undefiled form versus the quiet disturbance of an added material. This artist is one of the most innovative American Indian potters working today.

Jacquie works with clay from the Pecos area and other clays that she finds and tests. She pit-fires her pottery with cow dung and "cedar" chips lining the bottom of the earthen cavity, and carefully sets in the pots, surrounding everything with wood. (“The term "cedar" is one that Maria Martinez used when I first saw her firing thirty years ago. I learned the hard way that Indians say cedar when they really mean juniper or mesquite, both of which are harder woods than cedar.”)

Jacquie usually covers the fire with dung, which smolders and makes what she calls "fire clouds" on the ware. Sheets of metal cover the bier, and if there is a wind the smoky marks will vary more than when the air is quiet. "When I peek in I can see what's going on," says the artist. Sometimes she uses a cone-shaped metal lid with three-inch holes in it for another color effect. Jacquie is always experimenting with the clay or the form or the fire.

"My work has been a process of constant transformation. I dare myself to try to create some new clay form, and that is what keeps me on my toes. Right now I am very excited about my monumental glass bead forms in clay. Glazing them in brilliant and bold primary colors is a very exciting process for me." Jacquie is so ebullient about this new work that her conversation goes into orbit; she shares with me her mental visions of one idea after another, planning the concepts that will come from this challenge of adding glaze to the vocabulary she already knows.

Jacquie's idea about her new work is characteristic of her approach to innovation. Her grandmother kept beads that she used to decorate vests, and she showed the small pretty objects to her grandchild. Now the adult grandchild exclaims: "Beads, I never dreamed they would give me ideas! Such a whole link of generations from my grandmother. It's a growing thing. It's like our language, that's a link, a connection. For me this is a time of freedom!"

Jacquie says she loves Santa Fe, that it is a perfect place to work. She loves the changes in the land, the wind, the light, the earth, the colors when it rains, the sky, the color of the ground, and how gathering the clay makes her feel. She knows she has energy here.

In 1837, Winnebagos came from Wisconsin to the Nebraska reservation. Later, in the 1880s, some returned to Wisconsin. There, basket making was more prevalent than in Nebraska, because the women could find better material for weaving in the Wisconsin woodlands. But Jacquie remembers that her grandmother made wonderful baskets in Nebraska. The influence of these baskets shows in the textural contrasts in Jacquie's earlier work. "The Winnebagos kept the language both places," she muses, "and that helped keep their ways. It is a strength for me.

"I am a very private person. I figure that all I have to say and share with the world is conveyed through the language of my pots." She places great importance on the representation of her heritage in her pottery.

Jacquie has won numerous awards for her pottery at Santa Fe Indian Market over the years.